Videogames don't age

In a discussion about the Playstation 2 the topic of the best games of the console came out, as it usually does in this kind of discussions. I said, half jokingly, half serious, that that honor belonged to King’s Field IV. One of the answers I received was: “In its time? Probably. Today? Not one bit”.

King’s Field IV is a game I hold dear to my heart. The more I think about it months after playing it the more I want to replay it because I know I’ll discover new things. Fine, I don’t seriously believe it’s the best game of its platform, if it would’ve came out on the Gamecube maybe it would’ve been, but as a Playstation 2 game, it sits comfortably amongst the top 5, I don’t know, I haven’t thought about that.

What I have thought about, though, is in its excellent level design: the ancient city is probably one of my favorite videogame scenarios. In its art design that turns the ancient city in a dark but also, strangely, cozy place. An immersive game like few others, where getting lost is the consequence of having many places to explore, many paths to take.

That answer didn’t offend me as much as made me want to switch topics. I replied sarcastically. It is a really strange opinion to have, because using the same logic… King’s Field IV, even in its year of release, 23 years ago, was “outdated”

They did what they wanted to do at FromSoftware

King’s Field IV was released in Japan in October of 2001. In that same year and console, Grand Theft Auto 3 defined the open world 3D game. Metal Gear Solid 2 amazed everyone with its incredible graphics at 60 FPS. Jak and Daxter: the Precursor’s Legacy delivered the new generation platformer, with no loading screens, at 60 FPS and with some incredibly stylized graphics. Outside of the Playstation 2, Halo: Combat Evolved standardized the first person videogame of the subsequent decades.

Most of the games published in 2001 with an over the shoulder, or first person, camera, allowed for it to be manipulated with the right analog stick. In none of them turning around took you 4 entire seconds and I believe all of them had characters with a face, unlike King’s Field IV.

Conscious creative decisions, not always the result of limitations

A pretty common cliché when retro games are discussed is trying to ‘justify’ their quirks (creative decisions) with the limitations of their time. Like saying that, if things could’ve been done on a different manner, if they had 16 GB of RAM, 4K monitors, GPUs with hundreds of thousands of cores with several teraflops of processing, they would’ve done things on a different manner. It’s true, if GPUs with 16 GB of VRAM and processors whose frequencies were measured in gigahertz and not megahertz existed in the 90s System Shock wouldn’t look like how it actually does. We would be talking about those games in the same manner, currently, with hardware even more powerful than that, on how these are games outdated in both graphics and mechanics. That do not appeal to modern sensibilities.

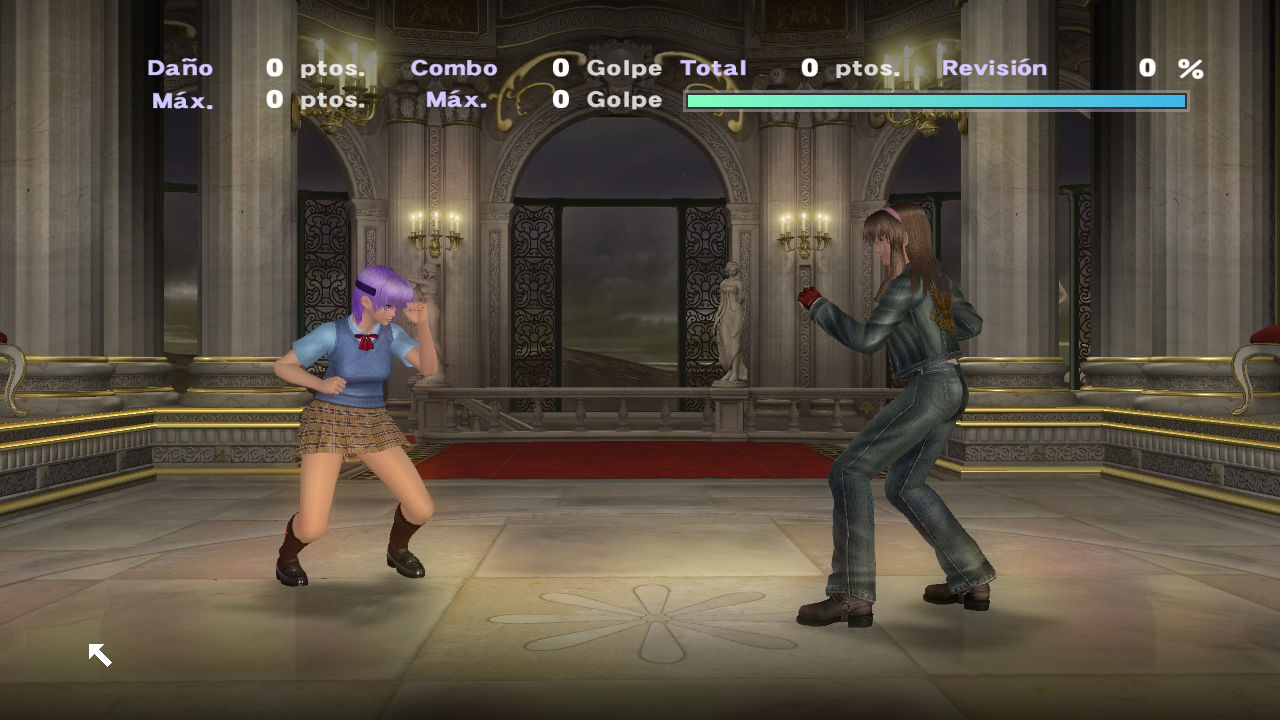

Dead or Alive 4, an Xbox 360 release title, avoided the problem of the uncanny valley entirely by not opting for realistic graphics for the models of

its characters, unlike many 3D fighting games of the time.

Dead or Alive 4, an Xbox 360 release title, avoided the problem of the uncanny valley entirely by not opting for realistic graphics for the models of

its characters, unlike many 3D fighting games of the time.

Although a priori it could look like the case, that Silent Hill has fog because the developers didn’t want our Playstations to catch fire and that in Super Mario Bros. we can’t go left because going right is enough of a problem, the reality is that we can’t generalize. We can’t minimize legitimate creative decisions by saying to ourselves that they’re just the product of outdated hardware. And because they’re the product of outdated hardware, maybe they’re themselves outdated characteristics of the game.

But no, not really. Armored Core 2 came out a year before King’s Field IV, in the year 2000 and still exclusively used the d-pad, in a console where the Dualshock controller wasn’t a peripheral, but the main controller. GTA III showed us that the Playstation 2 was capable of showing us a city, so why did everything was still covered in fog in Silent Hill 2?

Even though creative decisions are influenced by (and not the direct product of) technical limitations, the results are still that: creative decisions. The fog in Silent Hill is the result of the poor draw distance the Playstation was capable of. This resulted in one of the most recognizable horror videogames of all time. When Armored Core was released, I think the DualShock didn’t exist yet, so the d-pad was the only way to control your AC. This resulted in a challenging videogame where every action has weight and where controlling your 8-meters tall killer robot even hurts a little. I wouldn’t enjoy it in any other way.

Even though I doubt the developers at FromSoftware were aware that a game like Halo was in development at the same time in which they were doing the same with King’s Field IV, they could just see what Alien Resurrection did in the year 2000: using both analog sticks in an FPS: one for movement and another for the camera. Nothing prohibited them of allowing the player to control the camera with the right analog stick instead of with the triggers: I doubt the inclusion of this feature would’ve prolonged the development time significantly. Although it would’ve broken the game’s balance and its atmosphere, but that’s not something that matters to people that consume remakes.

No, what really happens, because of x or y (maybe they didn’t want to change the principles put in place after 6 years of developing dungeon crawlers) Rintaro Yamada, Satoru Yanagi and other creatives at FromSoftware had in mind what they wanted to do: a slow-cooked dungeon crawler, where you take too long to turn around because that’s a way of making the combat as tense as they wanted it to be. Basically, they took creative decisions that ended up in a videogame. And it didn’t matter to them that months after Halo came out on the original xbox with its twin stick controller configuration and its fast gameplay. They also didn’t care that they were the only ones in the industry making dungeon crawlers at the time, or that what they ended up making wasn’t sufficiently flashy to be promotional material for its console (something that Miyazaki would say about Demon’s Souls).

Nobody at FromSoftware, in 2001, cared about any of that. So, why, 23 years later, should it matter to us? Maybe the gaming aficionado should instead stop trying to find excuses to not play anything that has more than 10 years behind its back and decide to finally engage with the games of the past in an honest manner.

We perceive the videogame as technology and not as art

Videogames have always been related to toys in both concept and perception. Making the NES look like a toy was one of the strategies Nintendo used to distance itself of Atari and the products that ultimately caused a crisis in the north american videogame market. Before Atari, Magnavox publicized its Odyssey as a toy that you wired up to the television. Consoles have always had peripherals that put them close to toys.

Toys are noble, and I will never minimize them, but there’s a clear difference between the creative possibilities the design of one provides you with in comparison with a game, not specifically a _video_game.

But anyway, more than toys for children, we like to see videogames as toys for adults. Not in the sense of an expensive lego set one buys after, finally, getting their first job, but in that of computer hardware. Expensive graphics cards, last generation processors, gazillion gigabytes of ram. Our toys, at the end of the day.

When a processor is not enough and a GPU can’t cope with the new titles we replace them. I feel that we see videogames in the same way: a photograph of its technological panorama always waiting to be replaced for something more advanced.

We perceive videogames as a result of their technology and not as a creative exercise like any other

When we see the works of the medium as replaceable by other technologically superior ones, we can’t help but see them as the logical consequence of the design of its hardware and its power.

We spoke before about creative decisions, and how these, we think, used to be defined by technical limitations as we like to blame every defect of such and such game to those elusive limitations. And not only hardware limitations, but also zeitgeist ‘limitations’.

These are more abstract ‘limitations’ than graphics with too few polygons and a sound quality inferior to that of a CD. I’m talking about controller schemes, design patterns, gravity, camera.

Again, I repeat that those are creative decisions. But they’re usually the characteristics that usually scare away modern players the most, in my experience, at least. It comes to mind the remake (yes, it had to be a remake) of Resident Evil 4.

For those that haven’t played the original, it has tank controls. Not too similar to those of its predecessors of course but you still can’t control the camera and you turn around at a fixed speed.

Ira, in his King’s Field IV review made it clear:

King’s Field IV es un juego lento. […] Esta lentitud de movimiento no es porque sí. El control del avatar es nuestra conexión directa con el mundo digital. Varía esto y cambiarás la percepción del mundo.

Translated:

King’s Field IV is a slow game. […] This slowness of movement is not without reason. The control of the avatar is our direct connection with the digital world. Tweak this and you’ll change the perception of the world.

Control schemes are, therefore, a creative decision, taken by the designers as a way to shape the reality of a game and what we feel when playing it. Do you really see the world in the same way when walking, riding a bicycle or driving?

In Resident Evil 4 this translates into a claustrophobic experience: you can only see what’s in front of Leon when you aim, what’s behind you is imperceptible. You’re faster than your foes but not as much as to be able to easily leave them behind. Not being able to walk and aim at the same time results in that the decision of taking aim is a compromise on your part. You do it because you think you won’t miss and because you believe, or know, that there’s no one behind or close enough ahead of you to harm you.

But from 2005 (it is a 2005 game, right?) to now no third person shooter plays like that. A year later Gears of War would be released and just like Halo 5 years before, it’d dictate the design of a whole genre for more than a decade.

Now aiming and moving was a rule, at least a little and losing a bit of precision (well, at the end of the day you have to balance things). Evading was no longer done by walking: you could roll, run, stick to walls pressing only a button that seemed to do almost anything. That’s what Gears of War was about. It bet on that design because your enemies attacked at range, because it was more about flanking and positioning as much as having good aim and being able to run. Rolling and being a magnet to the walls were the tools the game provided you with so you could play it in the way it expected you to play it, and those same tools were also there so you could be able to fix your mistakes: retreating in a timely manner if you realized you didn’t position yourself in the best way.

That’s not what Resident Evil 4 is about. That’s not what a lot of third person shooters are about, in fact. But it became the standard. What came before, even if it was a game with radically different principles, was now ‘outdated’, and not only graphically.

In 2012 Capcom would release Resident Evil 6, a game that ultimately would go unnoticed. A painfully boring and frustrating game that copies because that’s what people expect and prays for us to eat whatever it offers us. It doesn’t understand Gears of War: taking cover turns your screen into a fuzzy mess, in the coop mode, the death of your partner interrupts you as if the game was hijacking your TV signal. Doing evasive maneuvers is sporadic and it doesn’t dictate the rhythm as a roll does it in Gears. And the zombies with guns, a kick in the balls in the form of a videogame foe, don’t have neither the mobility nor the intelligence of the Locust, but they do have their vitality. They end up killing you because 3 of them were waiting for you to take a peek, not because you were outsmarted.

Years later, in 4’s remake, having the control scheme of Resident Evil 4 is even more unacceptable. It’s just that now parrying got fashionable too.

Those are the ‘modern sensibilities’.

Games that ‘were’ bad in the past still are. Games that ‘were’ good in the past still are.

A final point: I want to explain to you that years do not weigh in on a videogame. Not when you experience it as it comes and engage sincerely with what it offers you. Saying that something ‘aged poorly’ isn’t a valid criticism for me, because I believe that which was bad in the past still is, and vice versa.

I could write an entire post about videogame controls, maybe I will. But for me, at least, the controls of this or that game are bad when they are in conflict with what that same game wants you to experience: when they limit you more than giving you the freedom to condition yourself to its rules.

I feel that the controls in Shadow the Hedgehog are bad because of that: the game wants you to go fast (what a surprise) but at the same time it wants you to shoot the aliens: shooting is an activity that requires precision, and no matter how much aim assist the game provides you with, you will soon see yourself standing still more than you’d like.

The controversial tank controls aren’t bad by themselves: they maybe would be in action games but they’re usually used in horror ones where combat isn’t the first option.

The only thing you should do is get used to it, and see directly into the eyes of any old game: accept it for what it is, accept that it’s a product of its time. That nothing it offers you is ‘outdated’ by virtue of what came after: in the end it’s the creative endeavor of a team of people that lived in a specific technological and ludic context: that they tried to do the best they could with what they had.

We’ll really escape from experiencing the creative product of one or many people, because of the years it has on its back?